As she walks, María Rosa Angulo gazes at hundreds of six-meter tubes stacked in an overgrown plain in Lorena de Santa Cruz. Sixteen years ago, Angulo helped block a similar project that would have used tubes like these to deliver water from the Nimboyores aquifer to what is now the Reserva Conchal Hotel.

A few meters away, a concrete structure resembling a guard’s shack protects access to the aquifer, one of the province’s most important because of its large volume of water. For years residents have fought to protect this aquifer for this very reason.

But plans to exploit the Nimboyores aquifer have resurfaced as part of the Northern Pacific Integral Program to Supply Water to Guanacaste, or PIAAG, an ambitious effort by the administration of President Luis Guillermo Solís to revive dormant projects to provide access to water for residents and local industry. Yet only about 44 percent of the budget needed to carry out these projects has been secured.

An investigation by The Voice of Guanacaste and journalism project Punto y Aparte determined that several of PIAAG’s projects already had failed during previous administrations. And while the current administration has made progress in designing and carrying out some of the projects, questions remain about the source of funds for the remaining 56 percent of the program’s budget.

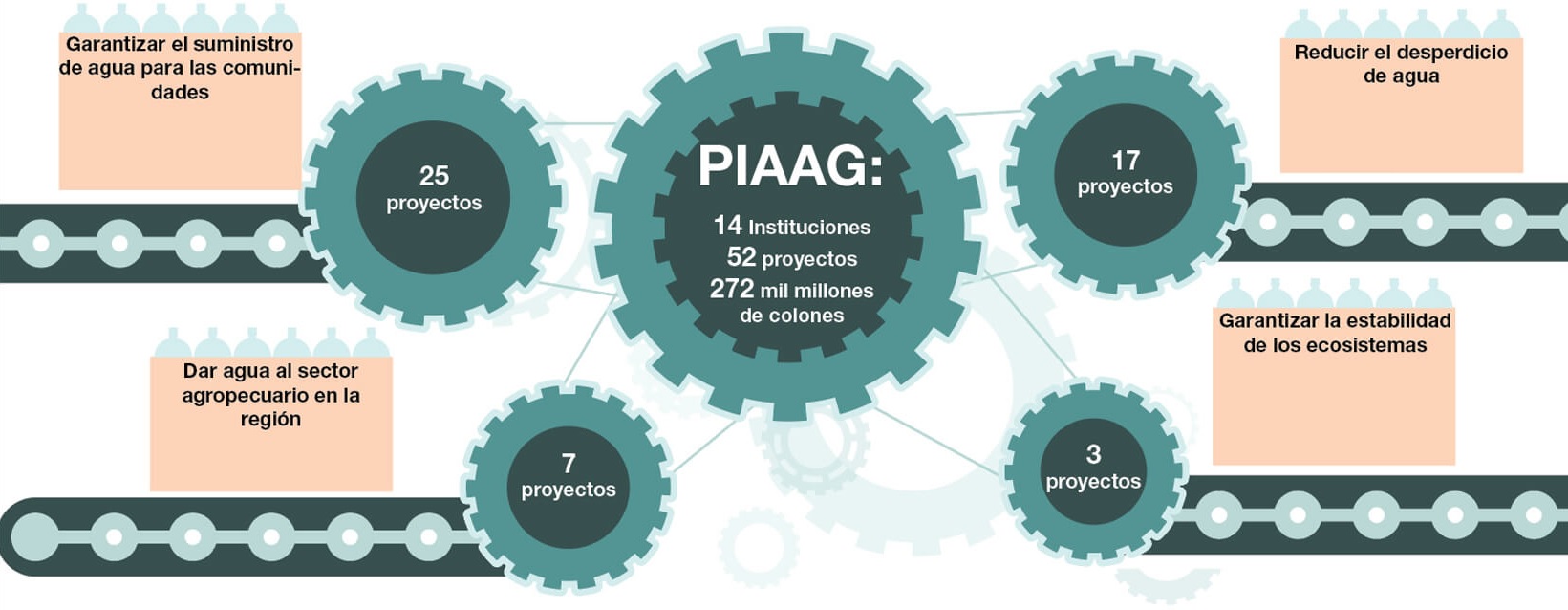

PIAAG is as costly as it is complex: It includes 52 separate projects grouped in four stages that include the participation of 14 different agencies – all negotiating the program’s future.

While the fact that the effort is advancing is good news, Angulo worries that the program could become an excuse to over-exploit resources she and others have fought to defend for so many years.

“This aquifer cannot be touched if there is no interest in protecting it,” said Angulo, president of the local rural water association known as an ASADA.

Her concerns have merit. The effects of climate change, drought, population growth, industries that demand an increasing supply of water and a lack of control over aquifers have ravaged the province’s water supply, a concern the government acknowledges.

That’s one of the reasons PIAAG was initiated with some of the failed plans borrowed from the first program to provide water to Guanacaste, created during the second administration of President Óscar Arias (2006-2010).

Angulo isn’t the only one who worries about the progress of PIAAG. Joining her are water specialists, farmers, ranchers and many residents who also have their doubts.

The most glaring concern is the budget. A total of ₡272 billion ($500 million) already has been earmarked or is being allocated, but an additional ₡336 billion ($620 million) needed for completion of three megaprojects isn’t yet available, and no one is certain where that money will come from.

To give an idea of how much funding is still needed, that’s about eight times the equivalent of building the Cañas-Liberia route, which cost ₡7 billion ($130 million).

As of today, PIAAG has advanced by about 35 percent. Most of the completed projects involve delivering water to affected communities via trucks and cisterns, along with training residents in the responsible consumption and conservation of water.

The pending projects are long-term ones, and here’s another problem: Eleven are slated to be finished in 2020, two in 2021 and three have no completion date. In other words, it’ll be up to future administrations and agency bosses to finish them.

According to Bejuco de Santa Cruz resident Ulises Rodríguez, some of his neighbors “carry water for several kilometers.” This has been a problem “for several years,” he said.

Rodríguez has had to adapt to ongoing periods of drought. He leaves his home every morning in the small village of Bejuco de Santa Cruz, climbs a narrow wooden ladder, and opens the top of a black tank to check the water level. A water truck comes every Wednesday to fill the tank, the only source of potable water for the entire village during periods of drought.

“We’ve needed a well since 2001,” he said while turning a small plastic faucet to fill one of the containers that each of the 27 homes in this village use. “Three months ago they gave us one, but now we need a pump and tubing.”

When it rains, temporary relief comes to the residents here as rainwater replenishes local aquifers. But that usually lasts only a few months, and as soon as the next dry period comes water scarcity is a problem again. And according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, temperatures across the globe are expected to continue rising.

Water scarcity is not a new problem for residents and past administrations. In 2008, the administration of President Óscar Arias attempted to address the issue in a failed effort known as the Plan de Abastecimiento de Agua y Gestión Integrada de las Aguas residuales para Guanacaste, or PAAG.

That program aimed to improve aquifer management to reduce the overuse and salinization of local wells. It sought to convert saltwater into potable water and promoted construction of megaprojects such as reservoirs. If it sounds like a precursor to Solís’ PIAAG, in many ways it is.

So what happened to those projects?

“In the past 25 years the only thing we’ve seen are attempts (at finding a solution),” said current Environment Minister Édgar Gutiérrez. “There haven’t been substantive projects to develop infrastructure.”

Previous efforts were underway but hit a wall because they weren’t properly funded or designs weren’t finished, he added.

According to Gutiérrez, what’s changed is that funds have been guaranteed and officials from the various agencies involved are committed to providing continuity to the program.

The head of PIAAG’s technical secretariat, José Miguel Zeledón, speaks with confidence about the projects that already have begun as an example of how the entire program has progressed. He highlighted the effort to provide potable water to affected communities and improvements made to aqueducts in Liberia, Varillal, Moracia and Copal de Nicoya and Pilangosta de Hojancha – all of which are nearly completed or already finished.

Zeledón, who has spent 28 years at the Environment Ministry’s Water Department and served as its director for the past 18, has seen many projects come and go. But he is optimistic about current efforts because the agencies involved have committed funds and designs already are being completed.

They key, he said, is that projects must be financially viable with designs and budgets clearly defined, which diminishes the possibility of failure. Zeledón said the goal is to make all of the projects financially secure by 2018.

According to Yamileth Astorga, executive president of the Costa Rican Water and Sewer Institute (AyA), one of the key government agencies involved in the program, “All of the projects overseen by AyA have budgets earmarked or allocated. That makes it difficult to cancel them.”

Some of the projects could have their budgets changed depending on the needs of local residents. For example, AyA already has modified its budget several times to address water scarcity by providing trucks to fill community cisterns.

Environment Minister Gutiérrez and AyA’s Astorga said that while it’s a necessary evil, the cost of trucking in water to communities is unsustainable. Since February 2015, the government has spent ₡200 million ($369,000) to deliver water by trucks – ₡140 million ($259,000) over its budget to do so.

“That’s not sustainable, but we can’t leave people without water,” Astorga said.

According to Environment Minister Gutiérrez, “It’s too expensive to deliver water to communities by using trucks.” He added that, “The political class needs to understand that (these projects) are a necessary investment.”

Gutiérrez was referring to the Legislative Assembly, which is tasked with approving large projects such as the Río Piedras reservoir and a new water resources bill, both of which are crucial not only for Guanacaste, but also for the rest of the country.

During the last drought, rancher Luis Antonio Contreras saw his herd of sheep drop from 200 to 80, while the number of cattle decreased from 33 to 15. In an industry that requires an abundance of water, Contreras ultimately was forced to sell all of his livestock.

Ranchers require about 70 liters per head of livestock per day. Together with crop farming, raising livestock is one of the industries that most consumes water.

Unlike potable water in communities, ranchers’ needs can’t be met by delivering water on trucks. To address this problem, the government’s Northern Pacific Integral Program to Supply Water to Guanacaste, or PIAAG, outlines seven projects under the label of “food security.”

One of the most important of these is the Sistema de abastecimiento de la cuenca media del río Tempisque y comunidades costeras, known as the Río Piedras Project. The government will have to accumulate debt to pay its estimated $500 million budget.

Río Piedras is one of the older ideas that made it into the current PIAAG, having existed before climate change became an ongoing concern in Guanacaste.

In 1976, a reservoir was designed to collect water that is wasted during production of hydroelectric energy at the Arenal dam, according to Marvin Coto, director of engineering at the National Groundwater, Irrigation and Drainage Service, or SENARA.

Each year, approximately 500 million liters of water from Arenal is channeled out into the ocean, when it could be used for irrigation, like the other half of water that leaves the hydroelectric dam. With the new project, a reservoir of 90 billion liters would channel water for use along the Tempisque River basin, benefitting Liberia, Carrillo, Santa Cruz, Bagaces and Nicoya.

The idea was revived in 2008 as part of the original water for Guanacaste program, but it stalled after the Costa Rican Electricity Institute (ICE), which was tasked with building it, discovered design irregularities. An initial investment of $15 million was lost after the project was cancelled.

Today, the current administration is working to make the idea a reality to provide 20,000 liters of water per second. Of that, 83 percent would be used to irrigate 18,000 hectares of land, 7 percent would be delivered to the tourism sector, and 10 percent would be slotted for human consumption with population growth factored in through 2040.

But so far, funding has only been secured for technical studies and designs, not for actual construction.

According to the Environment Ministry’s director of water, José Miguel Zeledón, “This time around, (the Environment Ministry) is investing ₡1 billion ($1.8 million), while (the Agriculture and Livestock Ministry) is contributing ₡1.4 billion ($2.6 million) from its budget for next year, and SENARA has earmarked ₡200 million ($369,000) to guarantee the project is financially viable before 2018.”

But challenges remain. In addition to budget uncertainties, in order for the Río Piedras reservoir to become a reality, officials must secure the land that would be flooded. To do that, they must expropriate about 1,350 hectares on 24 properties.

The problem is that more than 100 hectares belong to the Lomas de Barbudal Wildlife Refuge, a protected area. ICE and the Organization of Tropical Studies (OET) are conducting two environmental impact studies.

“Our biggest fear is that (legal) openings like this could lead to further exploitation in the future. Today it’s water in Guanacaste, but tomorrow it could be mining or other activities,” OET specialist Mahmood Sassa said, expressing concern. The OET will present its findings in December.

The potential impact on the Barbudal refuge has been documented since the idea was first proposed in 2008. A SENARA proposal estimated that about 150 hectares of protected land would be flooded.

The next obstacle is political. “Rio Piedras won’t move forward if the Legislative Assembly fails to approve compensation for Barbudal Wildlife Refuge," said Environment Minister Édgar Gutiérrez. That compensation includes “making up for” environmental damage caused to the refuge.

While visitors to Guanacaste might not notice a drought at this moment, it doesn’t mean the worst is over.

Across the landscape, the number of livestock has noticeably decreased, and farmers and ranchers say they urgently need support to protect them when the next drought hits.

The PIAAG calls for diversion on the Liberia River to channel water from the northern watershed to the Salto, Liberia and Quebrada Santa Inés rivers. This type of diversion uses tubing and tanks to channel water from one area to another, where it is more greatly needed. After the Río Piedras reservoir, this would be the program’s second megaproject.

These rivers would supply 750 liters per second of water for the irrigation of at least 1,425 hectares of pastureland for livestock, and troughs for about 20,000 heads of cattle.

Another reservoir, Las Loras, is among the three megaprojects dreamed up 30 years ago and without a budget to bring it to fruition. Las Loras would collect and store water during the rainy season for the irrigation of 1,500 hectares in the dry season and in times of drought.

The combined budget of the three megaprojects is in the range of millions. $7.45 million is earmarked for design, while $4.8 million hasn’t yet been obtained. For the construction of the three, $620 million is needed and hasn’t yet been obtained.

During one of many speeches delivered while visiting Guanacaste, President Luis Guillermo Solís said that water needed to be provided not only to local residents, but also to businesses.

In Bejuco de Santa Cruz, Ulises Rodríguez is waiting for such a balance to be struck. He knows that every Wednesday a water truck arrives to fill his community’s cistern. But he also knows that the future of his community’s access to water depends on several government agencies and short-term politicians who have never faced – as he has – the real-life consequences of recurring drought.